In Experiment 1 (n = 32), participants were shown a picture of a black or white basketball player prior to observation of a point-light video of a player executing a basketball free throw. In the present article, we investigate the influence of sociocultural stereotypes on the impression formation of basketball players and coaches. Differences in these items and implications of these results suggest that there is a potential impact on academic achievement and the student–athlete’s aspirations. Differences in specific items on the scale indicated that African American student–athletes were more internally focused on their sport, felt that others perceive them only as athletes, and see sport as the focal point in their lives. Results indicated that African American football student–athletes have a stronger athletic identity compared to their Caucasian American counterparts. Division I‐A African American and Caucasian American football student–athletes’ responses to the Athletic Identity Measurement Scale were analyzed (Brewer, Raalte, and Linder 1993). This study explores the relationship between race and athletic identity.

Few studies have examined the impact and influences of race on athletic role identification. Athletic identity has been defined as the degree to which an individual identifies with the athletic role. Identity salience and strength depends on the importance of that role. Most individuals occupy multiple identities or roles in life such as sibling, student, spouse, employee, athlete, etc.

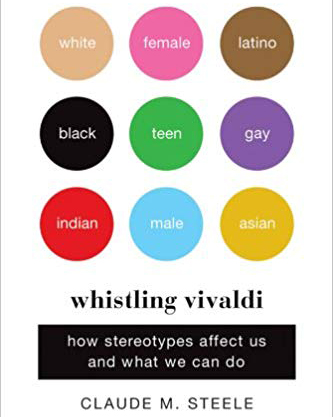

Whistling vivaldi summary professional#

The identification with the athlete role is likely to intensify as they get closer to the goal of professional sport. These aspirations may become even more focused and intense if they ascend to the level of division I college athletes. Considering the over‐representation of African American athletes in revenue‐producing sports in colleges, universities and at the professional ranks, it is no surprise that many African American male youth develop aspirations for, and identify with the athletic role. But for many African American boys and young men, the dream of becoming a professional athlete is a door that appears to be wide open. Although stereotype threat-the anxiety that you are conforming to negative assumptions about your social group-can occur to any member of any group, it occurs most frequently, and with more dangerous consequences, for groups that have more and stronger negative beliefs attached to them.Education is often viewed as the door that leads out of poverty for many students of color. Another friend, a Hispanic male, told me that he shaves all his facial hair when entertaining white clients to signal that he is respectable. A friend straightens her hair when she is job-seeking. I have been known to wear university-branded clothing when I am shopping for real estate, hopefully drawing on the cultural value of colleges and students to counter any assumptions of me as buyer. I do not know many black people who do not have some kind of similar coping mechanism. It seems an annoying daily accommodation, perhaps, an attempt to make whites feel at ease to grease the wheels of social interactions-unless we fully recognize the potential consequences of white dis-ease for black lives. The incongruence between Staples' musical choices and the stereotype of him as a predator were meant to disrupt the implicit, unexamined racist assumptions about him. Dangerous black men do not listen to classical music, or so the hope goes. It was a signal to the unvictimized victims of his blackness that he was safe. To counter the negative effects of white fear, he took to whistling Vivaldi. An African-American man, Staples recounted how his physical presence terrified whites as he moved about Chicago as a free citizen and graduate student. The title of Steele’s book alludes to a story his friend New York Times writer Brent Staples once shared. Social psychologist Claude Steele’s book Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do revolutionized our understanding of the daily context and cognitive effects of stereotypes and bias. The neighbor he asked for aid called 911 (“He is trying to kick down my door,” she cried on the phone), and one of the responding police officers shot the unarmed Ferrell 10 times.įerrell, who was African-American, may have been too hurt, too in shock, to remember to whistle Vivaldi to signal he was a victim and not a threat. The 24-year-old broke out the back window to escape and walked, injured, to knock on the nearest door for help. Last week, Jonathan Ferrell, a former Florida A&M football player who recently moved to the Charlotte, N.C., area to be with his fiancée, had a horrible car crash. The shooting death of Jonathan Ferrell reminds us of the heavy toll of stereotype threat.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)